Outstanding Undergraduate Work in the Midst of Pandemic

Academic year 2020-21 delivered a series of challenges, requiring faculty, staff and students to demonstrate resilience and to reimagine the life of the university in a remote setting. Our undergraduates, and History majors in particular, set a high bar, not only meeting the challenges of remote instruction during the pandemic, but producing outstanding, innovative work. We would like to celebrate a few examples as an indication of their many achievements.

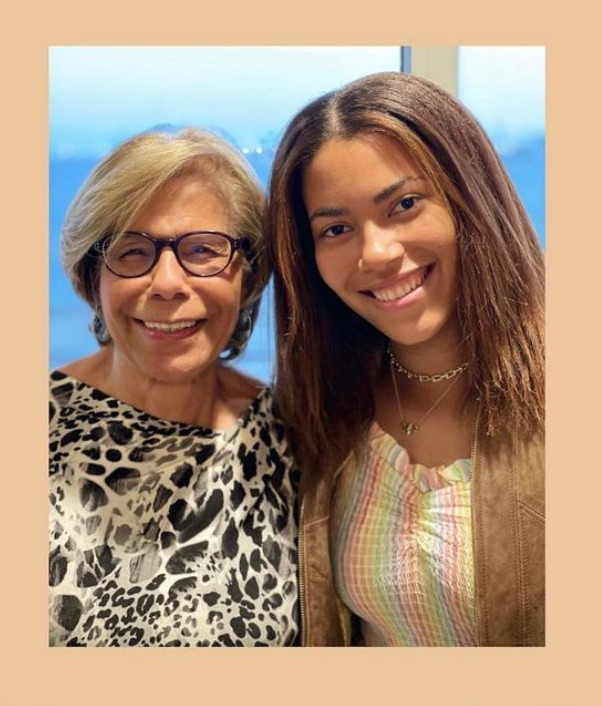

First-year student Bianca Jenkins conducted an oral history of her grandmother, Roberta Jones Jenkins. Bianca then produced the oral history as a podcast for her capstone project in Professor Adam Rothman’s History 099 Facing Georgetown’s History class. As Bianca explains in her introduction, “In this podcast, my grandmother, Roberta Jones Jenkins, and I discuss our family history. My great-great-great-great-grandfather is James Henry Hammond, an enslaver and governor of South Carolina known for his ‘Cotton is King’ speech in 1858. Our conversation traces and discusses the history of the Hammond family.” Bianca and her grandmother, who are African American, offer deep insights into the complicated legacy of racism and the resilience of black families across American history. Bianca’s podcast shows how the historical is personal, and exploring our own family histories can put a human face on the things we sometimes only read about in books.

Senior Rachel Singer published her article, “The Black Death in the Maghreb: a Call to Action,” in Journal of Medieval Worlds, a scholarly journal published by the University of California Press. Rachel’s article, developed in Tim Newfield’s global plague seminar (HIST 404/BIOL 269), engages the evolving historiography of the Black Death, the great late medieval plague pandemic. In analyzing the scholarship on medieval plague, Rachel spotted something odd about histories of the pandemic in North Africa. Histories of the plague there did not stand on their own feet; rather, scholars had written the history of plague in the Maghreb by drawing on data from Southwest Asia and/or Iberia, assuming the North African experience of plague could be predicted on the basis of the experiences of people in those regions. Plague ecology informs us, as Rachel points out, that this methodological leap of faith is unsubstantiated. Across different landscapes and climates, and across different cultures and economies, the spread and prevalence of plague would have differed. Incorporating climate and ecological data relevant to plague’s history in the region, as well as modern scholarship on the history of the Maghreb and scarce written sources contemporary to the Black Death, Rachel argues the Maghrebi experience of plague must be assessed on its own terms and that the history of the Black Death in the region was distinct from that of the densely populated and highly urbanized regions scholars have extrapolated from. Plague may not have devastated North Africa, and this forces us to reconsider the idea that the Maghreb served as a launching pad for plague’s spread into West and Central Africa. This is extraordinary work and Rachel is off and running on an impressive career.

First-year student Lou Jacquin, sophomore Maisha Maliha and senior Renny Simone produced a compelling documentary on the work of the great Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray. Their documentary, created as the final project for Professor Ananya Chakravarti’s HIST 224, Women, Film and Indian History, is entitled, “Promise, Power and Patriarchy: History and Women in Three Films by Satyajit Ray.” Indian women have played a large role in the indigenous film industry, one of the oldest in the world, and the medium provides a fascinating lens by which to explore women’s history in India. The documentary explores the nuances of femininity and challenges to traditional gender roles in Ray’s films, Kanchenjungha, Charulata and Kapurush, all from the 1950s-60s. Their documentary includes clips and stills from the films and archival material, as well as interviews with Georgetown scholars and their own careful interpretations. This is an impressive example of multimedia scholarship.

In another example of historical interpretation through the arts, senior Hunter Congdon displayed his pianistic aplomb with interpretations of classics from the Great American Songbook. This served as Hunter’s final project for MUSC200, Live Music in the Context of the Pandemic, co-taught by Professor Bryan McCann of the History Department and Professor Anthony DelDonna of the Music Program. Hunter interspersed his performances of songs like “These Foolish Things,” “Solitude” and, “Makin’ Whoopee” with remarks placing these works in their historical context and reflecting on their resonance in the midst of pandemic. Hunter’s performance was a great reminder of the power of music to provide both comfort and meaning, and the need to understand this as a historical process.

Lastly (but not certainly not least), Senior Sarah Laird’s paper for HIST 342, Sex and Power, with Professor Jo Ann Moran Cruz, offered an innovative, deeply grounded reading of a thirteenth-century poem from trobairitz Bieiris de Romans to Maria, a poem from a woman to a woman. Laird’s paper, “The Legacy of Bieiris de Romans and Courtly Love,” analyses the Provencal word ‘talan,’ which means ‘desire,’ showing that it is normally used in a sexual sense and that there is no reason to suggest that its use in this poem would be any different. Laird’s careful close reading strengthens the argument that the poem is from one woman expressing a sexual desire for another woman. This deepens scholarly understanding of a fascinating text, and enriches our understanding of gender in late medieval Europe.